The end of modern civilization. What caused it? Nuclear war, plague, zombies, alien invasion? Pick your poison. But the world we know is gone. Survivors must carry on. And therein lies a tale. Or a plethora of tales. Here you’ve got your Post-Apocalyptic fiction.

A lone hero with a sword faces down supernatural foes in a desperate struggle for existence, or maybe for a purse of gold. He’s no conception of our modern civilization. He might even despise the very notion of civilization (while simultaneously enjoying every advantage of it.) Here you’ve got your Sword-and-Sorcery.

How to reconcile these? How does Post-Apocalyptic Fiction tie in to Sword and Sorcery? Is there a connection? Should there be?

Scratch that last one. I’m not going to arbitrate that. But there certainly is a connection. Ever since the threat of atomic war intruded upon the consciousness of writers, that existential threat has influenced their stories. Writers of heroic fiction were not excepted. Instead of creating a secondary world, or setting stories in the fathomless past of this world, writers instead posited a fantastic world resulting from an apocalypse that occurred at some remove. Note, this is different from the Dying Earth genre, in which stories are set at such a fantastically distant point in the future that a specific apocalypse is fundamentally irrelevant; there could have been several in the intervals between now and the imminent destruction of the Earth in the death throes of the sun. The world of the Post-Apocalyptic S&S yarn derives its unique properties from the apocalypse.

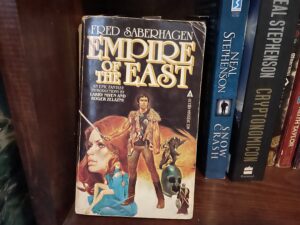

Examples. Fred Saberhagen’s Empire of the East. Both the planet-wide devastation and the creation of magic result from the same apocalyptic event (which I won’t spoil, but seriously, you need to read this one.) The later Book of Swords series approaches Dying Earth territory, in that the apocalypse occurred so far in the past it makes little difference whether the stories are set in prehistory, far-future, or on a secondary world.

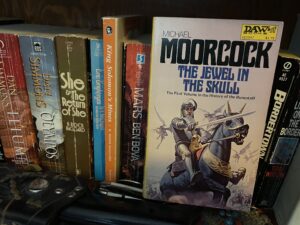

One of Michael Moorcock’s avatars of the Eternal Champion seems to be swashing his buckler on such a post-apocalyptic Earth: Count Brass journeys through an altered France and England, dealing with mutated creatures and bizarre, novel technology.

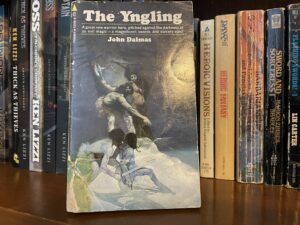

John Dalmas’ The Yngling fights through a post-apocalyptic Northern Europe that must deal with psychic powers. (Not, if I’m being honest, one of my favorite books. But it is an example.)

It’s an understandable approach. Even a single hint of a bygone past (something more subtle than the Statue of Liberty) could suggest a depth to the writer’s world, a sort of built-in cheat for world-building. As I recall, the Oliver Stone draft of the Conan the Barbarian screenplay had a post-apocalyptic setting, rather than REH’s past Hyborian Age.

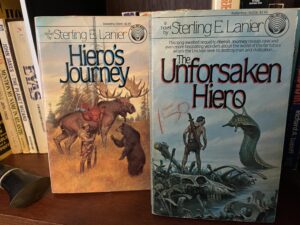

The cross-over appeal is easy to understand. Gary Gygax certainly did. If you read through Appendix N of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, you’ll find the above mentioned Empire of the East (or, to be precise, The Changeling Earth, which is the third part of the book) as well as Hiero’s Journey, by Sterling Lanier, a somewhat more sci-fi Post-Apocalyptic novel, though with evident appeal to the reader of heroic fiction. And let’s not forget that an early companion game of D&D was Gamma World, a game specifically intended to model the sort of fiction embodied by Hiero’s Journey, with its radiation-induced mutants, quests for lost technology, and strange new societies.

If you’re interested in reading my take on the Post-Apocalyptic genre, give Reunion a try.

And now, for those of you who have been reading the diary of Magnus Stoneslayer, here is Entry Four. (Entry One may be found here, should you wish to catch up.)

SAVAGE JOURNAL

ENTRY 4.

I’d like to state that, as a rule, I don’t get bored. But that would be inaccurate,

and if I cannot be honest with you, dear diary, then really, what is the point? Let us put on a brave face (of course that is for me merely a pro forma rhetorical device — I have no need to wear the mask since I am by nature fearless) and confront the facts: I am a roaming barbarian precisely because remaining in one location for any significant duration bores me.

Oh, I possess the stoic patience of the savage. By “remaining in one location for any significant duration” I don’t mean standing poised over a still pond with a fish spear in hand waiting for a trout to poke its head out from a shadowy ledge and like trials of the hunter and warrior. I endure such ordeals with laconic aplomb. No, I mean the ennui of tedious sameness, the daily sunrise to sundown routine of the peasant farmer, the repetitive watches of the palace guard. I speak from experience; I’ve done my share of soldiering in any number of armies, standing all manner of sentry duty, and I’m like to find myself enlisted again. But I’m not constitutionally suited to following orders, and the emphasis on routine — and here we pick up the theme again — bores me.

Which is why the tavern strumpet lying next to me with the satiated smile on her

dreaming lips will wake on the morrow to an empty bed. Did she truly believe that the strapping barbarian warrior who’d stopped in for a joint of beef and a flagon of ale had given over his wanderlust for a sedentary existence as her help meet premised solely on the allure of

her meager charms? I cannot credit it. No, women are more canny than that. She knew exactly she wanted, and she received it. She saw in me a temporary variation of her insular life. In this respect at least the civilized and the barbarian worlds are identical: women

get bored too.

So, before I pad as silent as a wolf into the night, I bid you, dear diary, farewell

until tomorrow.

Magnus Stoneslayer

1 comment

Magnus Stoneslayer

Padding “silent as a wolf into the night” from the tavern

{….off to find entry one; hyperlinks didn’t get me there}