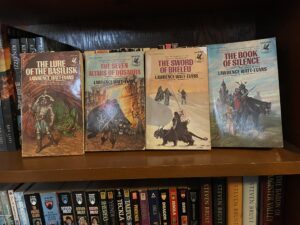

It was the Darrell K. Sweet cover that lured me to the first book, The Lure of the Basilisk. This introduced me to the world of Lawrence Watt-Evans’ The Lords of Dûs tetralogy and his unique character, Garth the Overman. The overmen were, it seems, magically created genetic mutations of men, made larger, stronger, less emotional, and with certain other physical traits including a second opposable thumb, thicker skin, and Halloween mask facial features. Writing from a non-human perspective can be challenging, but Watt-Evans gives overmen generally overlapping character traits, so greed, anger, and curiosity all can play a role.

The first novel commences with Garth experiencing existential angst and wishing that his name would live forever. He consults three wise women — that is, overmen — and is sent on quest that initiates four novels worth of events, though that is far from obvious by the end of the first novel. The Overmen live far to the north in an icy wasteland, separated from men, after losing the Racial War three hundred years ago. Garth is sent to visit The Forgotten King in the most northerly human settlement, and instructed to do as The Forgotten King requests. (The Forgotten King is also referred to at times as The King in Yellow, which, along with references to Hastur and Carcosa (with that spelling) provide little Easter eggs throughout the novels, though without any particular payoff.) The Forgotten King tells Garth to visit a distant city and bring back the first living thing he encounters in the dungeons beneath. This turns out to be the titular Basilisk. Garth’s fulfillment of this quest occupies the bulk of the novel and it is narrated in exhaustive detail. It is clear that Watt-Evans pondered each twist and turn, each doorway, conceived of each difficulty — major or minor — and worked out how his hero would overcome it. And he shows his work.

The second novel, The Seven Altars of Dûsarra finds Garth once again, reluctantly, doing the bidding of The Forgotten King, after Garth’s pragmatic attempt to establish trade between the northern human settlement and the overmen runs into difficulties. The Forgotten King requires Garth to bring back whatever he finds on each of the altars of the seven gods of Dûsarra. The seven dark gods. Again we follow the procedural details, sitting in on Garth’s decision process. Every factor, every possibility is weighed, then Garth acts. Garth ends up returning to The Forgotten King with a sword that seems to have a will of its own — stronger than Garth’s, for that matter — and a woman, a sacrifice encountered on one of the altars. We begin to get more detailed world building, especially concerning the religious pantheon and, as we discover, the building blocks of the plot and end game of the series.

The third novel, The Sword of Bheleu, at times feels like it is merely filler, something to pass the time until we get to the fourth book. It also lacks a Darrell K. Sweet cover. While Laurence Schwinger’s cover is adequate, he doesn’t appear to have read the description of either an overman or the Warbeast upon which he rides. The book isn’t, of course, mere filler. We learn about the Bheleu, the god of destruction and how through his sword Garth becomes his tool. Garth succumbs to rage, driven by Bheleu to acts of horrific violence and demolition. The sword is — to employ Dungeons and Dragons terminology — of Artifact power levels. (Speaking of D&D, I wonder if anyone has ever statted Warbeasts. Tough. The sort of thing you’d want on your side rather than in opposition.) We get more world building, learning about a council of wizards which decides that it needs to oppose Garth in order to avoid the apocalyptic age of destruction that Bheleu portends.

The stakes ramp up in the fourth book, The Book of Silence. After an introductory seventy or so pages (the page counts increase book by book) that have absolutely no bearing on the plot and provide no payoff (as if Watt-Evans forgot all about it, or was just playing around with an idea he thought was fun but couldn’t figure out how to incorporate it into the rest of the narrative) Garth struggles to avoid working for the Forgotten King. He fears that following the instructions and wishes of the Forgotten King might lead to the end of the world, of all life, of even time itself. We get some cool monsters, some minutely detailed fight scenes, vicious acts of revenge from one of the priesthoods whose altar Garth had defiled, magic, travel, traps, etc. All of which are explained in the painstaking detail we’ve come to expect. And therein lies some of my issue with the series. It is entirely too procedural. We are presented with these sweeping, world-shattering events. And yet they are dealt with cooly, as if narrated by Mr. Spock. There should be an undercurrent of blood and thunder, rather than simply being told that there is blood and thunder. I don’t feel it. Garth sifts and weighs every action, speculates on every characters motivation, looks at every angle. It is as if Watt-Evans wants us to know that he has carefully considered the world and each character, and that he has worked everything out to a logical inevitability; that this is serious, not crazy-pants fantasy in which anything could happen without rhyme or reason. And I get that. But I prefer not to spend quite so much time with the decision making process behind each action, each statement. For one thing, people aren’t that calculating. Not even overmen, if I can judge from the other overmen characters we meet in the books. For another, it slows everything down.

I think if the tetralogy had been trimmed down to a trilogy, with much of the fat excised, I would have enjoyed it more than I did. Not that I dislike it. I don’t regret reading it. There are some interesting set pieces. Garth is a unique character, a tragic figure vaguely reminiscent of Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, whose decisions seem inevitably to lead to wholesale carnage and destruction. Also, I got three Darrell K. Sweet covers. I may well be guilty of overanalyzing, and you might breeze through these more pleasurably than I did. I really did like the first one. The procedural aspect worked well. Different strokes for different folks is what I’m saying, I suppose.

Before I move on to my usual crass commercialism, I want to note the passing of an American icon. Jimmy Buffett played an outsized role in the lives of many. I first paid attention to him in my sophomore year of college, picking up a live, double-album LP at a used record store. Endless plays, along with reading a non-fiction account of a man walking around the world, solo, led me to seriously consider dropping out of school. After all, what more interesting occupation for a would-be writer could there be than wandering the Earth along, like Caine. (Kwai Chang Caine, not KWE’s Kane.) I went so far as to begin pricing equipment at outdoor stores and military surplus stores. Happily I let the idea drop. I’d hate to imagine discovering plantar fasciitis in the middle of nowhere — halfway across Bulgaria or something. It was bad enough discovering it in the army. In fact Buffett helped get me through the army. I’d mentally review lyrics while performing some mindless, make-work chore in basic training. Buffett cassette tapes and a walkman accompanied me on deployments to Honduras and Haiti. I attended five or six concerts over the years. He was a hell of a showman. The passing of celebrities, most of whom I’ve never met, generally leaves me unaffected. But the loss of Jimmy Buffett leaves a hole. I’ll miss him.

I don’t really have a segue to selling books. Maybe Reunion, with its themes of loss might be an appropriate read. Or perhaps Thick As Thieves. Either way, you’d get a good read.

1 comment